Michael Jay Geier began operating a neighborhood electronics repair service at age eight that was profiled in The Miami News. Michael was a pioneer in the field of augmentative communications systems, helping to develop speech synthesis systems for children with cerebral palsy.

Book Review #5

Review

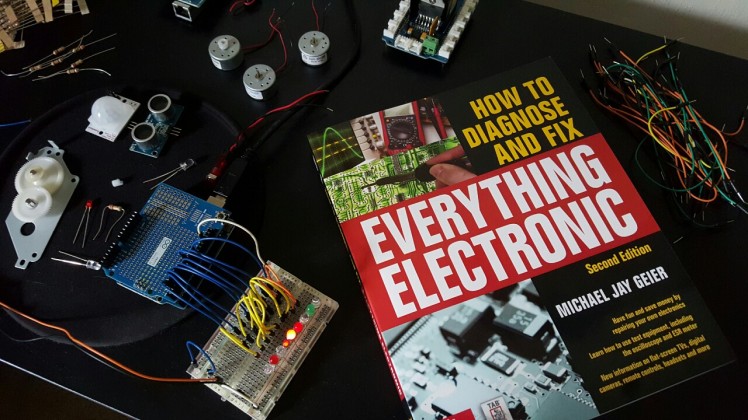

This book is a guide to troubleshooting and repairing electronics. Michael Geier is obviously an electronics guru. He is able to dive into the physical intricacies of each kind of device, compare and contrast their analog or digital counterparts, as well as discuss what test equipment is best for use in diagnosing the problem. Geier tries to teach problem solving with this book, rather than simply supplying a how-to reference manual. I enjoyed the personal stories he provided about his thinking process and how he arrived at the answers to several complex failures.

What I find lacking is an explanation of the behavioral properties behind the failed parts and how they come together to introduce the problems we see. I think he also assumes that the reader has a strong academic background in electronics; I don’t, and many repair shop technicians don’t either, so it was rather strange for the book not to mention much in terms of electronics theory.

Overall, I think it’s a great book for hobbyists who enjoy repairing electronics on the side. I would not recommend it as a teaching book on how electronics fail.

Rating: 5/10

Notes

Designers usually design products in such a way that the product has no choice but to work. However, whether it be poor design, poor treatment, expired product, improbable scenarios, or plain old manufacturing defects, products will fail. When it comes to diagnosing these failures, the process is very much like the tests doctors run for patients. Each patient, and device, will have their own makeup, idiosyncrasies, history, and way of life. It is up to the doctor to observe the symptoms, reason carefully, test cautiously, and draw reasonable conclusions.

Solder failures are common. They can be caused by poor manufacturing, or the circuit running hot enough to degrade the joints gradually such that overtime, the joints become resistive or intermittent. Corrosion on the board can prevent a good solder, since solder won’t flow into oxidized metal.

Heat stress is a common failure of larger items like video projectors, TV’s, audio amplifiers, motherboards, backlight inverters, and power supplies. Source of heat stress can range from an excessive current drawn by a shorted component to regular operation heat that can degrade electrolytic capacitors over time.

Incompatible electronics that provide too high of voltage can overwork the voltage regulator, which will dissipate all of that extra power as heat. On the flipside, too low of voltage can lead to regulators driving in more current to compensate, overheating the system once again. A sudden electrical surge can cause resistors to turn to little shards of carbon and transistors to crack alongside their plastic cases.

Reversed polarity can also kill electronics. If batteries are placed backwards, and makes contact even for a fraction of a second, the device can fry and die. :)

Physical stress can also kill electronics. Dropping a laptop and no longer finding the backlight on is often a result of the fluorescent lamp broken inside, despite that the LCD is perfectly fine. LED screens are not as vulnerable to this.

Finally, chemical damage is common to those who bring their electronics to the beach. Seaside apartments often see plenty of corrosion damage to electronics due to salt. Even without salt, leaving batteries in a low current device for a long time (clocks, calculators, for example), will lead leaky batteries and corroded contacts. The great capacitor scandal in 1990 saw ubiquitous damage from bulging capacitors that eventually burst from their rubber seals and released corrosive electrolyte all over the circuit boards, severely ruining the units.

What does ‘it’s dead!’ mean?

Total loss of activity is actually more simple than intermittent or partial loss of activity. With a fully ‘dead’ device, we know it is likely a bad power supply or blown fuse. Bad capacitors or poor voltage regulator can be the source of the original bad power supply. If the fuse is blown, there is a short somewhere, and it’s important not to just change the fuse, and it will probably blow again.

If the display doesn’t turn on, but everything else seems fine, then it is probably a clock crystal that isn’t oscillating or a failed microprocessor.

If tapping on parts help, then it’s a poor connection problem somewhere. Perhaps an oxidized connector or cold solder joint.

If the device works when cold but stops when warmed up, then the source is probably a flaky semiconductor and bad capacitors.

If there could have been water damage at any time, then shorts should be suspected. Shorts on parts with buttons can make the device think the button is being pressed all the time– and that can lead to all kinds of weird behavior (think remotes!)

Get a good lab bench that is bright colored (to see dropped screws), away from pets and children, relatively dry (damp environments can kill electronics), isn’t on carpeting (charge build up!), and near a grounded (three-wire) electrical service (15 amps should be enough).

Blueish white flourescent lighting from an LED bulb is best for spot lighting. Incandescent produces too much heat and eco-bulb fluorescents operate at too high a frequency (which can interfere with measurements) as well as radiate too much UV light (which can hurt your vision!).

Some must-have tools to start off with would be a DMM, an ESR meter (to properly evaluate a capacitor’s inherent resistance by driving with only a low voltage AC waveform, such that the capacitor doesn’t get a chance to charge), an oscilloscope (analog + digital if possible, since analog can’t freeze frame while digital can miss signals or worse yet, alias them), a medium-tip soldering iron with a heating element in the range of 40-70 watts (if possible, supply power through a base unit with a step down transformer from the AC line), a pound roll of solder, a plastic-melting iron, some solder wick or a rubber solder bulb to desolder parts if necessary (pair with chip quick to help keep solder molten at low temperatures), screwdrivers, cutters, needlenose pliers, hemostats, a magnifier, chip leads, swabs, contact cleaner spray, alcohol, naptha, heatsink grease and heat-shrink tubing, electrical tape, small cups, and internet access :)

Does anyone have michael geier email address so i can ask him for some advice on a repair